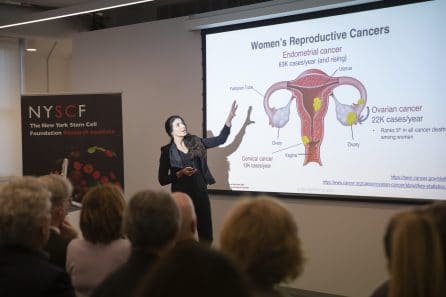

On the Road to Personalized Therapies for Women with Reproductive Cancers

Ovarian cancer is a difficult disease to tackle, as is evident from the statistics that surround it: Five years...Ovarian cancer is a difficult disease to tackle, as is evident from the statistics that surround it:

Five years after diagnosis, ovarian cancer survival rates are just 47% – a number that has not changed in the past 25 years.

Over 80% of patients will relapse.

The American Cancer Society estimates that roughly 21,000 women will receive an ovarian cancer diagnosis in 2020, and roughly 13,000 of these patients will die.

Through our Women’s Reproductive Cancers Initiative, NYSCF is aiming to improve outcomes for patients with ovarian cancer and enable personalized treatments. In a recent panel discussion moderated by NYSCF Associate Vice President of Scientific Outreach Raeka Aiyar, PhD, and held as part of NYSCF’s series of virtual events, Initiative members Laura Andres-Martin, PhD, Susan Domchek, MD, and Alessandro Santin, MD, discussed the complex genetics of the disease, emerging cancer therapies and strategies, and how NYSCF is leveraging stem cell biology to accelerate precision cancer care. The panelists also highlighted the problem that many emerging therapeutic insights are not relevant to racial minorities, and discussed how each of their research efforts is addressing that need.

What makes ovarian cancer so hard to treat?

There are many factors that make ovarian cancer tough to treat, but one of the most important ones is the highly personalized nature of the disease.

“Even two patients with the same tumor type can have very different disease experiences,” explained Dr. Andres Martin, a Research Investigator in Oncology at the NYSCF Research Institute and leader of the Women’s Reproductive Cancers Initiative. “And within a single patient, no two tumors are exactly the same. It’s a very individualized disease.”

The reason for this is largely because cancer is a disease of our DNA. How a tumor forms, whether it metastasizes (spreads to another part of the body), and how it responds to treatment all depend on the genetics of that tumor and patient.

What can genetics tell us about individualizing cancer therapies?

As Dr. Domchek pointed out, understanding patient genetics is critical for getting the right treatments to the right patients.

“It should be the standard of care that every patient with ovarian cancer undergoes genetic testing to see if they carry certain genetic mutations,” remarked Dr. Domchek, Executive Director of the Basser Center for BRCA at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and a member of the NYSCF Women’s Reproductive Cancers Initiative Scientific Advisory Board.

Dr. Santin, Co-Chief of Gynecologic Oncology at Yale Cancer Center and a fellow member of the NYSCF Women’s Reproductive Cancers Initiative Scientific Advisory Board, agrees.

“Genetic oncology has completely changed the way that we treat patients over the past 5-10 years,” he added. “I never finalize my recommendation for an ovarian cancer patient without complete sequencing of their tumor.”

Mutations can either be acquired over time by a tumor, or you can be born with them—both are important for understanding ovarian cancer. Dr. Domchek always tests patients for mutations in genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2, as these mutations can significantly increase a woman’s risk for developing ovarian cancer.

“If you have ovarian cancer, I highly recommend this testing,” she said. “It can determine your own treatment path as well as inform your family about possibilities for inheritance of this mutation.”

So, if you’re a patient, you might be eager to pick up a 23andMe or other direct-to-consumer genetic testing kit. Dr. Domchek advises going through your physician instead.

“Depending on the company and the test, you get different information,” she explains. “For example, 23andMe will only test for three common mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, even though we know of thousands, and will basically only test for them in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. One of the advantages to going through a genetic counselor or physician is that they know a lot about these tests and what you’ll need to make the biggest impact on your care.”

What are some other current strategies for treating ovarian cancer?

Yet in many cases, having genetic information about the tumor and patient are not enough to be sure of what therapies will be effective. This is where functional testing using laboratory models of cancer, like what NYSCF and Dr. Santin are doing, is critical. For some BRCA-related cancers, for example, drugs called PARP inhibitors have been a real game-changer by targeting defective DNA repair mechanisms in the tumor — but BRCA testing alone does not predict whether these will work.

“For ovarian cancer, this is spectacular,” remarked Dr. Domchek. “It works best in patients with BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutations, but it can also be helpful for other patients too. So then we have to ask the question, who will benefit from PARP inhibitors and how can we pick them out?”

Dr. Santin uses a technique called mouse xenografts to pick these patients out as well as determine which combinations of drugs may work best for their tumor. To do this, Dr. Santin takes a sample of a patient’s tumor (removed during surgery) and implants it in a mouse. He can then test drugs on the mouse to see how the tumor responds in a living organism.

“We call it this an ‘avatar animal’ because the tumor tissue growing in the mouse very closely recapitulates the tumor growing in the patient,” he explained. “So, the major advantage here is that as soon as we have the genetic characteristics determined from sequencing, we can begin to test drugs on the mouse and use it to inform what may work in a patient.”

How is NYSCF’s Women’s Reproductive Cancers Initiative using stem cells to better understand and treat ovarian cancer?

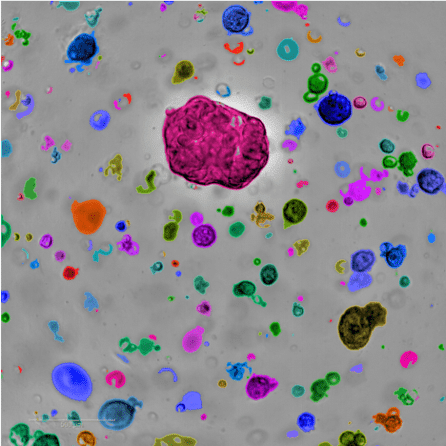

Another option for understanding how a patient’s tumor develops and testing drugs involves stem cells — the basis of Dr. Andres-Martin’s work.

Her team is creating a biobank of ovarian cancer organoids – 3D ‘avatars’ of patient tumor samples with an unlimited lifespan – that recapitulate how cancer behaves in a patient’s body. These organoids can be used, like Dr. Santin’s mice, to test drugs, showing which treatments may be most effective on specific tumor types.

“With these models in the laboratory, we can test hundreds of drug combinations to find which ones are best for each individual patient,” she explained. “And because stem cells have the capability to self-renew, we can use them to create unlimited amounts of testing material, overcoming a major limitation of current studies.”

How can we make sure that research and treatments are effective for ethnic minorities?

As America currently grapples with issues of racial injustice, the discussion turned to the many cancer therapeutics and discoveries that are not applicable to ethnic minority populations.

“A recent study reported that women who breastfeed significantly lowered their risk for ovarian cancer, but the finding was particular to white women because not enough Black or Asian women could be included in the analysis,” pointed out Dr. Aiyar. “We see this happening over and over again where ethnic minorities are underrepresented in research and clinical trials.”

“It’s important to recognize that racial disparities in research and healthcare exist, and they aren’t going to go away on their own,” remarked Dr. Domchek. “We have to involve women of color in all our research so that it applies to everyone.”

“And on the treatment side, for example, women of color are much less likely to get genetic testing than white women. That cannot be acceptable. So, at the Basser Center, we have something called the LATINX & BRCA Initiative which directly reaches out to Latino patients and their providers, because many of these women are never referred for genetic testing.”

Dr. Santin underscored that racial disparities in healthcare are a life-or-death issue.

“We can see up to a 30% difference in endometrial cancer survival rates between African-American and Caucasian patients,” he explained. “Why is that? A lot of it has to do with access to quality care, and also genetic differences. We need to understand these differences so we can provide targeted treatments.”

NYSCF will make Dr. Andres-Martin’s cancer biobank available to the wider research community to accelerate studies around the world. She also stressed that it is being deliberately built to capture genetic and ethnic diversity.

“New York City is such a multicultural space, and we are trying to take advantage of that for collecting samples from populations as diverse as possible,” she said. “This will help us capture the disease at a population scale, which is incredibly important for precision medicine.”

Watch the full discussion below.