A Stem Cell Cure for HIV? Another Patient is in Remission Thanks to Bone Marrow Transplant

NewsIn 1995, Timothy Ray Brown received bad news: he tested positive for HIV. The AIDS epidemic was in full swing. He recalled to New York Magazine that his partner at the time cautioned him that he likely had two years to live. Fortunately, lifesaving antivirals for HIV were just about to hit the market, and Brown was afforded options to manage his diagnosis.

Then, ten years later, he received bad news again. This time, it was acute myeloid leukemia, a blood cancer. He received chemo – the cancer came back. He turned to a bone marrow transplant – a treatment introducing healthy blood-forming stem cells into the body – and not only did it keep his leukemia at bay, it effectively cured his HIV.

Now, the same treatment that cured Brown has reached several others, including a 53-year-old German man referred to as ‘the Dusseldorf patient,’ who has reportedly been in remission from HIV for the last four years.

How does this stem cell treatment work, and could it be used to keep HIV at bay in the broader population? NYSCF’s Interim CEO Derrick Rossi, PhD, explains.

How HIV Hijacks Cells

“HIV is a virus, and it targets immune cells in the blood called T cells. It is able to infect T cells via a protein expressed on the cell surface – think: a special doorway – called CCR5. Once inside a cell, it replicates making hundreds of thousands of copies of itself, and then kills its host cell releasing the freshly minted viral particles,” said Dr. Rossi.

With depleted T cells in the blood, patients become highly susceptible to infections and are unable to fight them off. Left untreated, it’s almost certain to lead to death. Since 1980, 40 million people have died from AIDS – the result of late-stage HIV infection.

“The current standard treatment for HIV is antiretroviral therapy (ART), which works by preventing the virus from replicating,” explained Dr. Rossi. “Without the ability to make more copies of itself, it can’t effectively take over a host cell and it remains at low levels that aren’t as much of a threat.”

These treatments have been a game changer for patients because they turn a death sentence into a chronic condition. But they aren’t a cure. HIV still exists in reservoirs in the cells, and this residual viral load isn’t necessarily benign: a recent study found that people with treated HIV live substantially fewer healthy years than people without HIV.

Bone Marrow Transplant: From Leukemia to HIV

So how can bone marrow transplant help? Bone marrow transplants are traditionally used as treatments for patients with blood cancers/disorders, such as in the cases of the Berlin patient and the Dusseldorf patient.

“Bone marrow transplants work by introducing healthy, blood-forming stem cells into patients to effectively replenish their blood supply with the newly introduced stem cells” explained Dr. Rossi.

In the case of the Berlin patient and the Dusseldorf patient, the blood stem cells they received came from donors with a specific mutation in CCR5 that prevents the special ‘doorway’ receptor from expressing itself on the cell surface.

“Now, the patients were producing blood cells without an entry point for HIV,” noted Dr. Rossi. “If HIV can’t get in, it can’t replicate, and it can’t kill T cells.”

With cells that are HIV-resistant, ART isn’t needed. Brown stopped taking ART and remained HIV-free until his death from leukemia in 2020. The Dusseldorf patient hasn’t taken ART in years.

Additionally, in the five years following the Dusseldorf patient’s bone marrow transplant, the scientists (led by virologist Björn-Erik Jensen, MD at Düsseldorf University Hospital in Germany) continued running tests to monitor his immune system and response to HIV. While the patient still had immune cells that reacted to HIV, the team couldn’t be sure if this was due to an active virus or the corpses of leftover viral remnants. Either way, the virus was no longer replicating.

A Gene Editing Approach to HIV

When Dr. Rossi first heard of the Berlin patient, he had an idea. Instead of seeking out donors with the specific CCR5 mutation – which are limited – he wondered if the revolutionary gene editing technology CRISPR could allow scientists to edit blood stem cells at the CCR5 gene directly, essentially giving them the same resistance as those born with the mutation.

“When the CRISPR technology was first developed, I immediately thought to go after CCR5 and make a similar edit in bone marrow stem cells that had cured the Berlin patient,” said Dr. Rossi at a NYSCF town hall event in January. “HIV is still a global problem. After several years of work, we published a paper where we showed that we could make this edit in CCR5 using CRISPR in blood stem cells and that would be a way to lead to a therapy for people with HIV.”

This was the genesis of one of the companies that Dr. Rossi’s founded – Intellia Therapeutics – which aims to apply gene editing to a broad range of conditions including cancer and other diseases affecting the liver, eyes, muscles, and central nervous system.

Read more about the Dusseldorf patient in:

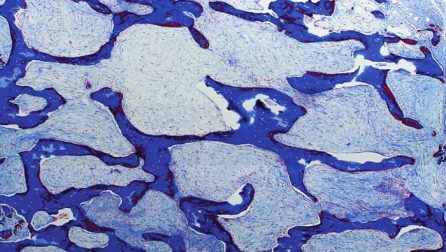

Cover image: HIV particles. Credit: James Cavallini/Science Source/SPL