NYSCF Scientists Talk Space, Stem Cells, and their Pioneering Study of MS and PD

The International Space Station (ISS) houses more than astronauts: the football-field-sized spacecraft is also home to a large range...The International Space Station (ISS) houses more than astronauts: the football-field-sized spacecraft is also home to a large range of research projects carried out in the ISS National Laboratories. Last December, one of these experiments, pioneered by NYSCF scientists and collaborators, involved growing brain cells derived from the stem cells of patients affected by Parkinson’s disease (PD) and multiple sclerosis (MS) in microgravity — the first study of its kind. Studying these cells is helping scientists learn more about how cells behave, how to model disease, and how to make spaceflight safer for astronauts.

We sat down with NYSCF Senior Research Investigator Valentina Fossati, PhD, and NYSCF Postdoctoral Fellow Davide Marotta, PhD, to talk all things stem cells, NASA, and the unique challenges and rewards of conducting biological research in space.

Why study cells in space?

VF: We are looking at how cells — specifically, cells called microglia derived from patient stem cells — function in microgravity. Microglia are the immune cells of the brain, and it’s starting to look like they overreact in neurodegenerative illnesses like MS and PD, contributing to the death of neurons. Physical forces affect how these cells behave, and microgravity is a unique circumstance in which to tease apart these healthy and diseased behaviors, pointing us toward new treatment targets.

This work is also important because we have more and more people going to space for longer and longer times, and we need to understand the impact of microgravity on our cells. We already have astronauts spending up to a year in space — and just think about if we ever send people to Mars. That’s a one-way trip, and we need to know how microgravity affects cells in the long term.

How were the cells studied in space?

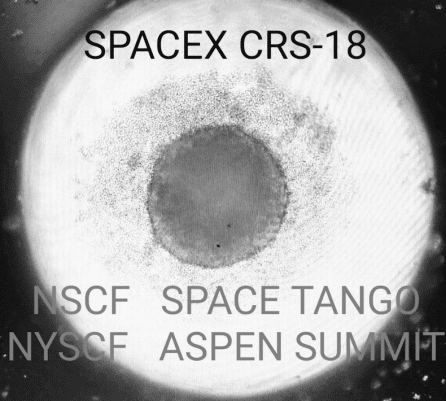

VF: The cells were sent aboard a SpaceX rocket to ISS, where they were kept in a structure engineered by SpaceTango called a CubeLab for one month. This technology is fully automated, so we could carry out our analyses from Earth. The CubeLab contained both the cells from MS and PD patients as well as cells from healthy controls.

DM: The CubeLab is incredible. It’s like a full lab in a small cube — the engineering is amazing.

Where are we right now in the experiment?

DM: The cells have now been frozen and returned to Earth on a different SpaceX spacecraft. We are looking at their gene expression and their structures to see how the environment of space affected their proliferation and development. I hope this will help us understand the cells better, because when we understand the cells better, we can make better disease models.

How did it feel once you started getting the images and data back from ISS?

DM: It was so cool. It really fed my curiosity and made me so excited to see the results of the experiment. It’s so crazy to think that something I worked on here on Earth went up to space for a month.

VF: It’s a contagious excitement, especially seeing videos and photos of ISS. You feel that it’s something bigger than what we are used to: it was a public experiment. People knew from the very beginning what we were planning, which is so different from lab work where they don’t know until it’s published.

What has been the biggest challenge in this project?

DM: The biggest challenge for me was the logistics. Working in space can be unpredictable, and working with cells can be unpredictable too. Conditions have to be exactly right for the launch to happen, and that can be really tricky.

VF: We had live cells, so that was a big factor. If a launch is delayed, that changes how we generate and package cells. And sometimes it isn’t just delayed by a day. Our launch was delayed once, and if it had been delayed again, it would’ve been 9 days before we could try again. It looks so simple when it happens — so smooth when you watch it, but it takes years and years of work by thousands of people to make it possible.

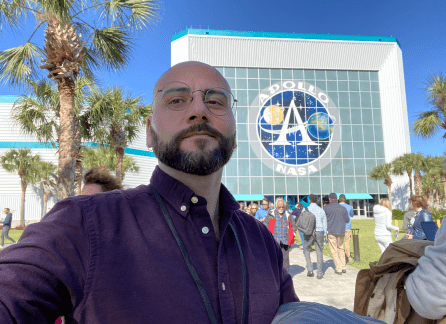

What was it like to see the rocket launch?

DM: I couldn’t believe I was actually there, standing within a few miles away of the launch pad. It was emotional and exciting just to see the rocket ready to go.

VF: Yes, definitely emotional. I think I cried out of relief that we succeeded — that it all fell into place when it needed to. To see the rocket go up is breathtaking, and to be a part of a pioneering study for MS and PD is very special. Also, when you’re at NASA, the energy is palpable. Even attending the ‘What’s on Board’ conference, you can see the range of science that is involved, and the scope is so broad. I felt very inspired being there.

This project is a collaboration between NYSCF, Aspen Neuroscience, Space Tango, and the National Stem Cell Foundation. Why are collaborations like this important for science?

DM: When you have more brains involved and more skill sets available, it really increases your chances of succeeding.

VF: Yes, and it feels great to see large projects succeed because of the expertise of all these different groups. Science is so global now. It’s beneficial to have other groups to discuss the science with — we are much more connected than you might think. Combining forces only strengthens what we can learn and how we can use this information to improve outcomes for patients.

What’s next for this project?

DM: We are planning a follow-up. Once we’ve finished our analyses, we’ll have a better idea of what the experiment will entail, but there will be another spaceflight in store. Stay tuned!

Read more from:

The National Stem Cell Foundation

[metaslider id=11483]

Photo credits: NASA/Isaac Watson/Kim Shiflett/Tony Gray/Kenny Allen/Cory Huston