Climbing for Cures: Five NYSCF Champions Summit the Tallest Mountain in North America

NewsClimbing a mountain is more similar to scientific research than you might think. You invest in a major challenge and there are a lot of unknowns and uncertainties. High highs and low lows. You could make it most of the way to the top but hit a storm and run out of time (food) before reaching the summit. If you don’t summit, you still learn a lot along the way. If you do, it can change everything.

This Spring, five patient advocates (Mark McCauley, Dieter Egli, PhD, James Teague, Blake Yaralian, and Knud Nairz, PhD) scaled Denali (the highest mountain peak in North America) to raise awareness and funding for stem cell research. They were inspired to take on this challenge in part as a way to honor the memory of NYSCF Founding CEO Susan L. Solomon, along with others close to them who have struggled with, or were lost to, disease. Their team name? ‘Mitosis are Cold’ (that’s a biology pun for you enthusiasts!)

NYSCF sat down with the climbers to learn more about the physical and mental struggles of climbing a mountain, the incredible planning and training that goes into it, and why it’s all worth it in the end, especially when dedicated to funding stem cell research.

Preparing for the Climb

Denali, as Mark aptly put it, ‘is not a mountain you start with.’ Last year, less than a third of climbers who attempted to conquer this Alaskan giant made it to the top. But while each of the NYSCF climbers had past experiences on big expeditions, none had taken on anything equivalent to Denali before.

“It’s one of those bucket list types of climbs,” remarked Blake. “It’s an incredibly challenging mountain. It’s one of the seven summits [the highest mountains on each continent]. So to do this climb for a great cause? I couldn’t say no.”

“I was ecstatic to embark on this latest climbing challenge with an extraordinary team for a remarkable cause,” agreed James. “Discovering NYSCF a decade ago sparked an ongoing interest in the ability of stem cells to accelerate cures to some of our most significant health issues of our time. I’m continuously astounded by the progress and breakthroughs they’ve achieved, and it’s an honor to be able to support such an important organization.”

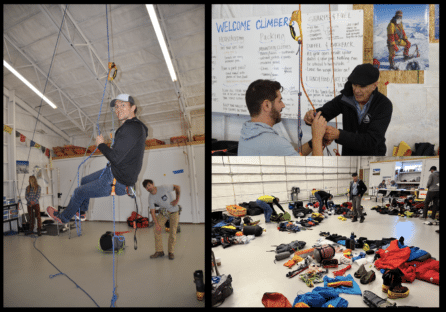

But it takes far more than a verbal commitment to prepare for the mountain. All the equipment you need for the expedition has to be carried up with you. That’s roughly 120 pounds of extra weight (food included!) climbers must carry – or drag by sled – with them on their march.

“To train, I would load my backpack up with 50 pounds of weight, and same with a sled. I live in a hilly neighborhood, so I’d just go walking up and down the hills,” said Blake. “I looked ridiculous to the point where the neighbors were like ‘What is that guy doing?’ But it was helpful.”

The gear itself is also intense.

“There’s triple-layered specialized climbing boots, as well as coats and sleeping bags made for -50 degree weather. This is the kind of stuff that is applicable only for the highest peaks in the world,” noted Mark.

“The packing process probably started in November,” added James. “Then you show up to the airport with these big duffels and you’re getting questions like ‘who is going to carry that?’ The answer is me!”

This kind of thorough preparation can also parallel that of a scientist. The training is long and difficult (ask any PhD student!). The equipment costs are astronomical (a standard research-grade microscope alone costs thousands, as does climbing gear). And you need to dream big and lean on your fellow teammates to get through it.

Once all the training is done, it’s time for the big job: if you’re a scientist, that could mean embarking on a big experiment. For the climbers, it meant taking the first steps toward the 20,308-foot summit.

Up and Away

The 22-day climb began in mid May, when the days are growing longer and the weather is warming up but still cool in Alaska.

The team steadily moved up the mountain, stopping along the way at different camps to rest, and cache materials.

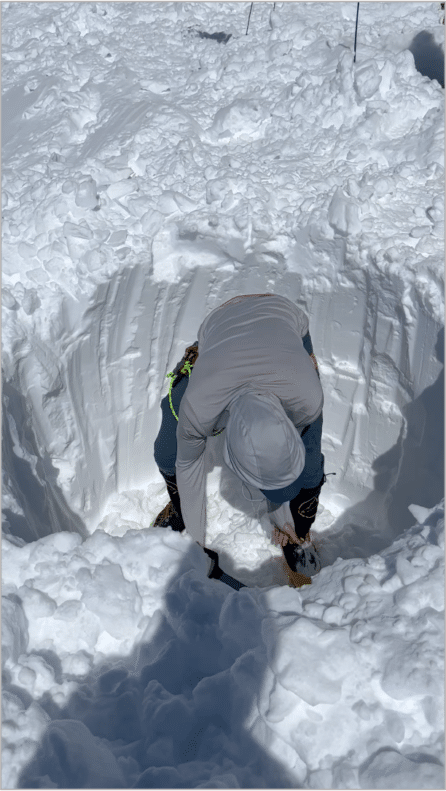

“Down at the bottom of the mountain, you can do what’s called ‘single carries,’ where you take everything with you,” explained Blake. “But as you start moving up the mountain it gets steeper, you can’t do that. So we basically climb the mountain twice. We go up once to cache roughly half of our stuff – meaning that we dig a big hole and bury it for pick-up later. Then we go back down to retrieve the remainder of our things and head up a second time.”

Interestingly, the hole has to be at least several feet deep so that the ravens can’t get into it, but not too deep in case there are additional feet of snowfall. As a practical benchmark for measuring depth, the climbers themselves served as living yardsticks when they were digging their 4+ feet holes to secure their caches.

Just like in science, where having good mentors is critical, the same is true for mountaineering. The guys were lucky to have one of the best, Vern Tejas, in their corner to lead the climb.

“Vern is 70 years old and this was his 62rd summit of Denali,” shared Mark. “He’s the only person to summit the seven continental peaks 10 times each. His stories are wild, and he has such a wealth of knowledge. He once got stranded on Everest with frostbite and spent the entire night crawling down the mountain to save his own life.”

Despite his rugged, danger-fueled lifestyle, Vern was always ready to cheer others up with a meal or a song (he brought his guitar and would play it while they climbed).

The ascent was not without its curveballs. At about 11,000 feet, Mark started to feel sick.

“I thought I was getting a head cold, but it moved to my chest and turned out to be a respiratory infection,” he said. “It was really rough, and I had to be isolated. I started antibiotics. Everyone chipped in to help me: carried extra gear, did the cache. That allowed me to recover. And then by the time we got to high camp, I had made my way through the antibiotics.”

Once they reached high camp (the highest stopping point before a team can summit), they were hit with another big challenge: a storm. The climbers were blasted with 60 mph winds. The temperature dropped to -50 degrees. Any skin exposed for too long would freeze. Every movement became critical.

“Of course it came at the worst possible time [while at high camp],” remarked Dieter. “That’s when I started to lose it a bit. I was sick of the snow and ice. I missed my family. I wanted to keep moving, but it wasn’t safe.”

A first attempt to summit had to be aborted. A second – their last chance – was successful.

“That feeling, to reach that top when you’ve put in so much work, reached your mental limits sitting in a tent wondering how much more you can take – it’s spectacular,” said James. “And I think the communal appreciation of the moment and being there together, recognizing everyone’s unique journey made it especially remarkable.”

“There were definitely tears shed,” admitted Mark. “I was very excited for that moment. And then that was followed by an excitement to get home and see my family.”

“There is this open space where you aren’t as interrupted by external thoughts,” said James. “In that quiet space in the heavens, you can find an odd connection with your loved ones, even those that have passed. I think it helps you to listen in a different way.”

A Summit Driven By Hope

Perhaps by now you are thinking, ‘this seems crazy.’ Maybe you didn’t even need to get to this point to think that. Why would anyone take on such a daunting task? Remember the part where they had to drag 100 pounds of gear up an icy slope and hide it from ravens?

For the climbers, the drive came from a desire to honor patients, scientists, and Susan with a journey that might parallel that of fighting a disease.

“Denali is the most difficult of the seven continental peaks, and summiting it is my way of honoring the legacy of Susan and contributing to NYSCF,” said Mark.

The climbers sought out a grand act to further a grand cause, and their reasons for doing what they did parallel why many people become scientists. Ask any of NYSCF’s researchers why they study disease, even when the obstacles can be overwhelming at times, and you’ll likely get similar answers: a passion for finding better treatments for a loved one. A mission to create a brighter future. A desire to journey into the unknown.

“Science and climbing have a lot in common,” said Dieter. “You push to find your limits, just as we did when we took that flag all the way to the top of North America. Anyone attracted to a career in research is someone who likes to take an idea and push it as far as they can.”

“Susan shared that spirit,” he continued. “She started NYSCF and gathered people who wanted to make things happen. She wanted to explore how far we could go. I think this climb carries a lot of symbolism for the drive to cure diseases, and there’s a lot of beauty in that.”

Learn more about the climb and give a gift to support stem cell research here.