How the Soldiers of the Skin Protect Us from Infection

NewsThe Problem: Our skin serves as an important barrier between us and the outside world, preventing a large array of possible infections from harming us. How exactly the skin mounts a defense against these infections, however, has not been well understood.

The Study: The skin protects us from infections by stationing ‘sentinel’ immune cells at regular intervals across its outermost layer and repositioning these cells as needed to guard vulnerable areas, finds a new study in Nature Cell Biology led by NYSCF – Robertson Stem Cell Investigator Alumna Valentina Greco, PhD, in collaboration with NYSCF – Druckenmiller Fellow Alumnus Sangbum Park, PhD, and NYSCF – Druckenmiller Fellow Katie Cockburn, PhD.

Why it Matters: This study illuminates how different cell types in our body coordinate with the immune system to defend us from external threats like infections.

“It’s a surveillance system with two separate roles,” Catherine Matte-Martone, manager of the Greco lab and co-first author of the study shared in an article from Yale. “The skin controls the sentinels by mediating their numbers based on its own density, while they in turn provide dynamic coverage to prevent cracks in the skin’s defenses.”

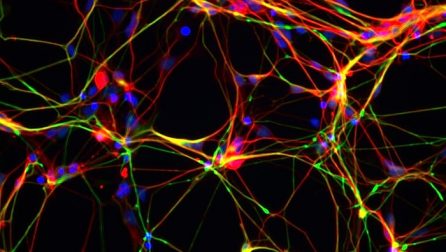

The skin’s defense team is led by two types of immune cells: Langerhans cells (LCs) and dendritic epidermal T cells (DETCs). To explore how these cells interacted with epithelial cells – the cells that make up skin – Dr. Greco’s team took high-resolution images of these cells in mice and tracked their behavior over time.

The team found that the immune cells positioned themselves in intervals that allowed for maximum distance between them, preventing clusters at any one point. This type of pattern is also found in neurons in the brain, whose ‘branches’ tend to space out to prevent overlap.

“Our study suggests that LCs and DETCs appear to have a mechanism of ‘self-avoidance,’ similar to neuronal cells,” said Dr. Park, an assistant professor at Michigan State University and former postdoctoral fellow in the Greco lab at Yale.

Interestingly, if immune cells were removed from the skin in a certain location, the remaining immune cells would shift to patch up the gap in their fortress. Targeting a gene called Rac1 which regulates the spacing of immune cell projections called dendrites disrupted immune cell patterning, suggesting that this gene is an important coordinator of the way immune cells position themselves.

The researchers are excited to continue exploring how these two systems – skin and immune – work together to serve a larger purpose in the body’s defenses.

“It is fascinating to observe how these different cell types co-exist and interact together in a developmental context rather than an immunological one,” remarked Ms. Martone.

Journal Article:

Skin-resident immune cells actively coordinate their distribution with epidermal cells during homeostasis

Sangbum Park, Catherine Matte-Martone, David G. Gonzalez, Elizabeth A. Lathrop, Dennis P. May, Cristiana M. Pineda, Jessica L. Moore, Jonathan D. Boucher, Edward Marsh, Axel Schmitter-Sánchez, Katie Cockburn, Olga Markova, Yohanns Bellaïche & Valentina Greco. Nature Cell Biology. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-021-00670-5

Cover image credit: Robert A. Lisak, Yale School of Medicine