Persisting Even When a Pandemic Delays a PhD: Meet Jenna Hall

NewsWhen COVID-19 hit, Jenna Hall’s plans were completely upended. Set to embark on a PhD at the University of Melbourne in Australia, border closures meant an extended stay in New York and a feeling of uncertainty.

“Adam Grant wrote a New York Times article about this feeling during the pandemic – this listlessness – and he used the term ‘languishing.’ And that was how I was feeling. My plans were paused indefinitely, and I didn’t know how to move forward.”

But as a NYSCF scientist, Jenna already had access to a stem cell lab, and all the tools to start her PhD remotely. Dan Paull, PhD, SVP of Discovery and Platform Development, offered to become a co-supervisor on her PhD project to study age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with stem cells, and she is now a dual NYSCF employee and grad student, back on track to realize her goal.

“NYSCF has been so wonderful by having me stay and start my PhD here with Dan as one of my mentors,” she remarked. “I couldn’t have asked for a better outcome given the circumstances.”

We spoke with Jenna about her journey as a scientist, starting her PhD at NYSCF, and her advice for young scientists.

What sparked your interest in science?

I became interested in science at 8 years old. Part of what sparked my interest in it was the show “Jimmy Neutron,” which is about a boy genius whose various inventions inevitably go awry. And, as strange as this sounds now, the character of Jimmy’s mom really made an impact on me. She seemed like the colloquial image of a homemaker, but later on you learn that the apron that she wears is actually because she’s an auto mechanic. The side effect of seeing this character was the understanding that a woman can be smart and can be a mom and an auto mechanic and all of these things, and it doesn’t just stop when you become a mom. Little Jenna brain-banked that.

Fast forward to second semester, freshman year in college, and I was in my first college chemistry class and just absolutely terrified. And then in the first couple of weeks, I went to every single help session and I realized that it clicked because I knew most of it already. I had learned it in my high school chemistry class. Somehow coach David Knoll taught me some of the most abstract introductory scientific concepts without me even knowing.

And then at the end of that course, because I had gone to so many help sessions, my professor, Alisha Ray, knew me and then became a mentor for me. I became a teaching assistant for all of her chemistry classes. I realized I was capable of taking more advanced science courses, and my confidence grew so much that I changed my major to biochemistry, exclusively so that I could continue to take the hardest science classes available to me.

How did you become interested in stem cells?

I learned about stem cells in an immunology course at the University of New Mexico taught by Dr. Rob Miller. I remember him saying that because stem cells can become any cell in the body, manipulating this capability could be a revolution in medicine. And just that single sentence that he said was a very sticky idea.

As a stem cell biologist now working in disease modeling at a state-of-the-art lab, I am totally obsessed with stem cells. It’s a career like nothing else: no day is the same. And then at NYSCF when you throw in the robots and the ability to do it at scale: it’s a dream.

How did you discover NYSCF?

In the summer of 2017, I was twenty-something, unemployed, and really desperate to get into a lab. I had a degree in biochemistry, but not a lot of wet lab experience, and all of the openings that I was seeing at hospitals or research labs all required years of bench work that I just didn’t have.

I finally got an interview and was hired at NYSCF for an opening on the operations team: running the stockroom, placing orders, calibrating incubators, just basic laboratory support. I told my team that I was interested in eventually moving into the lab, and they were so committed to my growth. They made a plan that allowed me to learn from scientists in the lab while doing my laboratory operations role. After a year, I moved into the lab and I have been doing research here for the past 3 years.

What have your projects at NYSCF involved?

My lab experience at NYSCF nicely parallels a project that we had with the National Eye Institute at the NIH. I started in the lab as a blood processing technician, isolating specific cells that we could turn into stem cells. Then I moved to the NYSCF Global Stem Cell Array® team. I worked with all of the robots, and it was very fast-paced: I worked with lots of hardware, communicating with software engineers and automation engineers, and incoming scientists, all while being trained by scientists that have been here a long time.

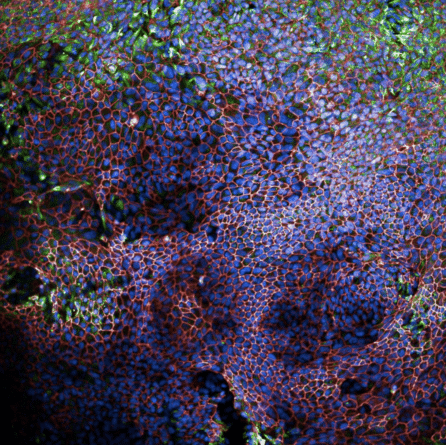

We then took all of the blood cells we had isolated, and using the robots, turned them into stem cells. The last part of this project with the NEI was to make a specific cell type called a retinal pigment epithelial cell – the eye cells lost in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). My role now is to make these cells, which are going to the NEI at the NIH for further testing and experimentation to see what we can do to uncover the mechanisms behind AMD and develop a cellular therapy.

I was afforded the opportunity to work on a few very fascinating projects with NYSCF-ers and collaborators. We often make stem cells from skin cells here at NYSCF. I was responsible for managing all of the automated cell production for a project in partnership with Google to study Parkinson’s disease. I was also able to work on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or NASH – a liver disease – by creating liver organoids, which are 3D clusters of liver tissue made from stem cells. Once COVID hit, NYSCF had a desire to contribute to the research being done to uncover how SARS-CoV-2 infected cells and if genomic identity played a role in susceptibility. Since I had organoid experience in the past, I was asked to develop lung organoids under the enthusiastic guidance of Dr. Brigham Hartley. I feel so grateful to have gained so much biological and technical experience from each of these projects.

How was your relationship with your team?

NYSCF employees are all brilliant, highly competent, highly motivated people, and the culture is incredible. It’s so easy to collaborate or just make friends. My team, specifically, was honest, communicative, and supportive, which was amazing.

What will you be investigating in your PhD?

I am doing eye disease research on age-related macular degeneration: the same thing that I’m doing in my NYSCF project. However, I am using a different method from my lab in Australia for making the cells, and different assays for testing their functions. My PhD supervisor at The University of Melbourne, Dr. Alice Pebay, made it possible to ship me cells all the way from Australia, which was exciting. Alice was critical in ensuring everything was in order down under so that I was able to begin my PhD research at NYSCF and I didn’t lose any more time to the pandemic.

How do you feel that NYSCF has helped prepare you for your PhD program?

I think NYSCF is the best place to be a junior scientist. The commitment to my growth that NYSCF has shown has been really unparalleled. I hear a lot of my colleagues who’ve come out of academic labs say that they just feel like a pair of hands, but my colleagues at NYSCF and I feel that you’re a pair of hands with a brain, and your input matters. That is really empowering as a young scientist.

The access to incredible technology as a NYSCF scientist has also been transformational for me. We have numerous state-of-the-art robots, and now, when I read about new methods in the field, I start thinking about how they can be automated. Because for science to be done correctly, it needs to be done at scale. And that’s what we’re doing here. It has informed my way of thinking and way of consuming science in general.

Lastly, I think NYSCF’s commitment to public science education is important. A lot of people are turned off by research because they imagine it as a scientist moving liquids around in a lonely, dark lab, but that’s not at all what it’s like. I admire that NYSCF brings people into the lab to teach the community about science, and I’ve gotten to tell people about the exciting work I’m doing and hopefully get them excited about it too.

What is one piece of advice that you would give to a young professional or someone who wants to take a path similar to yours?

Get a good mentor. Find someone who’s doing what you want to do and ask them questions and request feedback. Send emails, reach out on LinkedIn, or just talk to people around you. It’s the number one thing that has helped me become better. I was mentored by Alisha Ray in college, I have been mentored here by Dan and Brigham, and I’m looking forward to my mentorship from Alice in Australia. And for people further along in their career, I’d say try to be a mentor: people are so hungry to learn, especially in science, and there’s so many little pearls of wisdom that you can donate to improve someone’s experience.