Women’s Reproductive Cancers Are Among The Most Deadly And Most Neglected. How Do We Fix This?

The American Cancer Society estimates that nearly 20,000 women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022, and 12,000...The American Cancer Society estimates that nearly 20,000 women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022, and 12,000 of them will die. Survival rates have barely improved over the past 40 years. What’s going so wrong?

“Fundamentally, this is an equity issue,” noted NYSCF CEO Susan L. Solomon, JD. “This is backed up by data: when you account for incidence and mortality, ovarian cancer, for example, gets 20x less funding than prostate cancer. ‘#MeToo’ and gender inequity doesn’t just affect careers, but also diseases and lives. So we have an opportunity before us to advance equity in research for these cancers.”

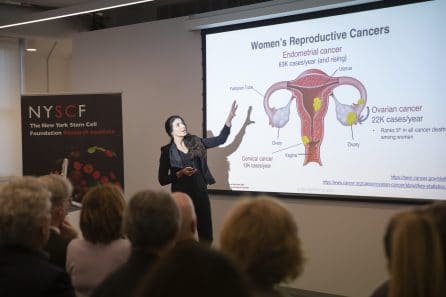

In honor of Women’s History Month, we recently convened a panel of experts to discuss health equity, the latest in research for women’s reproductive cancers, and the path to better patient outcomes.

This discussion and many of the cancer experts we’ve spoken to over the years paints a challenging picture, but underscores the reason that now is the time to be hopeful.

A Complex Disease Without Easy Answers

“For a patient with ovarian cancer, the standard of care is surgery followed by several rounds of generic chemotherapy,” says NYSCF’s Laura Andres-Martin, PhD, who leads NYSCF’s Women’s Reproductive Cancers Initiative. “But no two patients are the same, and no two tumors are the same, so we cannot treat everyone with the same drugs.”

The disease is also plagued by late diagnoses and high rates of relapse. 70% of ovarian cancer patients are diagnosed at late stages and these patients have a 29.2% 5-year survival rate.

A patient’s genetics play a critical role in their cancer experience, and much still remains unknown about how certain mutations impact disease risk and progression.

“A mutation is like a spelling error in the DNA sequence – the genome – of a cell. And if that spelling mistake happens at just the wrong part of the text of the DNA, then the behavior of the cell can really go askew,” explained Sohrab Shah, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “One gene being dysfunctional allows for a cascade of changes to accrue.”

Gross Underfunding Stilts Progress and Hurts Patients

One equity issue with women’s reproductive cancers is that they are terribly underfunded in comparison to other cancers.

“Less research dollars means slower progress towards treatments, which means fewer treatment options available and outcomes that are much worse than they could or should be,” noted NYSCF’s Raeka Aiyar, PhD.

“A striking feature of cancer survival statistics from 2022 is that there are only two cancers that have worse survival rates than before: uterine cancer and cervical cancer,” added Ursula Matulonis, MD, of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

And without sufficient research funding, scientists become discouraged from entering the field.

“I think what draws researchers into specific fields is the presence of funding,” said Dr. Matulonis. “We need funding to lead research projects.”

“This is a very complex cancer, and sometimes you need research results to compete for funding,” added Dr. Andres-Martin. “But because of the complexity of the disease, it takes longer to understand what’s happening, especially when it’s already underfunded, so you fall into this vicious cycle.”

“This really is a cancer of the genome, not a particular mutation,” noted Dr. Shah. “We need to analyze the whole genome, and that tends to be quite expensive. So to make progress, we actually need more dollars per tumor in this disease than we would otherwise.”

“In the grand scheme of things, knowing the state of the whole genome, however, is a small expense to incur because the treatments are expensive, and we want to match the treatment to the right patient. And so I think those dollars are well spent.”

Overcoming Racial Disparities in Cancer Patient Outcomes

“There are of course not only gender disparities, but racial disparities in outcomes even within these and other cancers,” pointed out Dr. Aiyar. “Black women have two-fold higher mortality rates for endometrial cancer and breast cancer than white women, for example, and Black men are twice as likely to die from prostate cancer.”

“It’s important to recognize that racial disparities in research and healthcare exist, and they aren’t going to go away on their own,” remarked Susan Domchek, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. “We have to involve women of color in all our research so that it applies to everyone.”

“And on the treatment side, for example, women of color are much less likely to get genetic testing than white women,” she added. “That cannot be acceptable. So, at the Basser Center, we have something called the LATINX & BRCA Initiative which directly reaches out to Latina patients and their providers, because many of these women are never referred for genetic testing.”

Luckily, many initiatives are underway to address disparities, but there is still a long way to go.

“I think a lot of the research has been focused on identifying the problem,” said Dr. Matulonis. “So, for example, one of our radiation oncologists has looked at access to radiation therapies for patients with either uterine cancer or cervical cancer, showing that it’s harder for Black women to get access to these different treatments.”

“A lot of hospitals have also started setting up satellite centers to reach different parts of the community,” she continued. “We’ve set up offices of equity and diversity, and really have significant strong research programs and access to care programs.”

“Secondly, we need to look at the biology of the different cancers,” she emphasized. “Are there differences in individuals who have these cancers? Do Black women have more aggressive cancers than white women? Do certain populations tolerate chemotherapy better or worse? We need to know so that we can ultimately individualize care to different patients.”

“There are really fascinating findings emerging where genetic ancestry of individuals can have an impact on what mutations accrue in cancers,” added Dr. Shah. “And so that really does suggest that the genetic ancestry of individuals can be a determinant of the type of biological properties of the tumor that evolves.”

At NYSCF, Dr. Andres-Martin’s team is addressing these issues by creating a diverse biobank of tumor samples as a community resource, ensuring minoritized patients are included in critical research.

“We live in New York City. We are fortunate to live in a diverse place where we have access to patients that are of diverse ethnicities,” she remarked. “And we are hoping that with our biobank, we will have a good representation of tumors across these ethnicities.”

Using Stem Cell Technology to Create Personalized Tumor ‘Avatars’

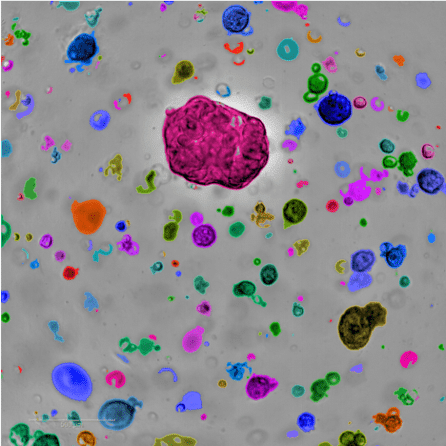

Dr. Andres-Martin’s team, which leads NYSCF’s Women’s Reproductive Cancers Initiative, is creating personalized ‘avatars’ of patient tumors to use as material for disease modeling and drug testing.

“Our approach allows us to create tumors with an infinite lifespan in the lab dish so we can actually do many different studies and understand the complex biology, because no two patients are the same,” she noted.

Normally, scientists study tumors by taking biopsies from patients, but these samples can only live outside the body for a short period of time, limiting the number of experiments researchers can use them for. By making organoids – 3D clusters of tumor tissue that survive indefinitely in the lab – scientists can conduct infinite experiments and establish a foundational resource for the wider research community.

“Through collaborations with physicians, we receive tumor samples from surgery and create organoids that reproduce the tumor in a similar manner to how it grows in a patient,” said Dr. Andres-Martin. “We can use these to study the biology of the tumors as well as test responses to treatments.”

“When old things don’t work, we need to try new things,” said Siddhartha Mukherjee, MD, DPhil, of Columbia University Medical Center, who serves on the Initiative’s Scientific Advisory Board. “We need to bring back into oncology that spirit of adventure that brought about great advances in cancer drug development.”

Importantly, organoids can be used to tease apart what makes patients different and determine which treatments work for which ones. Dr. Andres-Martin is creating a collection of organoids as diverse as possible in terms of genetics, clinical subtypes, and treatment responses, so that her team can conduct research that accounts for the unique complexity of these cancers.

Using Genetic Data to Tailor Cancer Treatments

Dr. Shah is a leader in computational oncology who specializes in using computational methods to understand how tumors evolve and respond to treatments.

“We can now analyze the genomes of individual cancer cells — thousands of them at the same time — and we’re able to recognize patterns in these cells,” he explained. “And that’s what machine learning and computer science allows us to do, is take these very large complex data sets and actually derive patterns.”

“What we’re finding is that we can start to group patients based on the pattern of alterations in their genomes. This is not only a biological grouping, but these patients respond differently to treatments, and this is where personalized medicine can be implemented.”

One personalized treatment for ovarian cancer that has been a game changer for patients is PARP inhibitors. Dr. Matulonis played an integral role in bringing PARP inhibitors to patients with mutations in a gene called BRCA that can drive cancer risk.

“As we’re thinking about new treatments, PARP inhibitors have been instrumental in those who have a BRCA mutation,” she noted. “And that can either be someone who’s inherited that mutation from either mom or dad, or the cancer has its own mutation.”

“It’s also improved how folks do in the recurrent setting as well. The challenge has been trying to figure out how we deal with cancer when the drug becomes resistant to a PARP inhibitor. And that’s where genetics is really going to help with immunotherapies.”

Immunotherapies have proven enormously beneficial for blood cancers like leukemia, but have proven more challenging to apply to women’s reproductive cancers.

“What we’re uncovering is that especially with immunotherapy, these ovarian cancers are quite tricky in that they can find multiple routes to immune evasion, where these cancer cells can hide from the immune system,” added Dr. Shah.

“This is another example of the complexity of this disease. What we’re learning is that these different types of DNA repair deficiencies, which create these patterns in the genome, actually relate to how these cancers hide from the immune system.”

“That’s quite promising because it suggests that if these patterns and properties hold up, that we can identify these tumors and then use different classes of immunotherapy to potentially advance the treatments.”

Dr. Matulonis stressed that there are many new therapies on the horizon to be excited about.

“For example, there are drugs called bispecific antibodies that have an antibody that targets different immune cells and brings them together. Normally they’re not in this same neighborhood, but you bring them in the same neighborhood,” she noted. “Vaccine studies are also underway. And again, a lot of work on basic immunology and how we can try to reignite the immune system to target ovarian cancer.”

Why is Now the Time to be Hopeful?

“I can certainly reassure everyone that there are large teams of individuals who are working diligently, despite the pandemic, to understand biology better and build better treatments,” said Dr. Matulonis.

“I think we’re really understanding now the different ways in which these cancers’ genomes go awry, and new drugs available that can target these mechanisms,” agreed Dr. Shah. “And so I actually think that we’re heading to a watershed moment where we can start matching patients up to these investigational agents and making breakthroughs. I think it’s actually going to be an exciting 10 years ahead.”

“We’re in a prime moment – there are so many things that are happening right now,” added Dr. Andres-Martin. “Every time I open new literature, something new is being discovered. Bringing together new technologies and understanding the biology of this disease will have positive outcomes, for sure.”