To Achieve Precision Medicine, Diverse Stem Cell Biobanks are Key

News VideoEven though breakthroughs in biomedical research have reduced mortality for most major diseases of our time, the gaps in mortality between ethnic minorities and white patients — otherwise known as racial health disparities — are actually increasing. Thanks to induced pluripotent stem cell technology, it is possible to represent genetically diverse patients in stem cell models of disease — yet most stem cell lines currently used in research are derived from white, European populations. Increasing the diversity of stem cell biobanks presents a key opportunity to ensure that disease research captures the full diversity of humanity and benefits all communities in need.

To explore this opportunity, we recently convened a discussion between experts Ru Gunawardane, PhD (Allen Institute for Cell Biology), Ekemini A. U. Riley, PhD (Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s), John Greally, PhD, DMed (Montefiore Hospital, Albert Einstein College of Medicine), Scott Noggle, PhD (The NYSCF Research Institute), and Raeka Aiyar, PhD (The NYSCF Research Institute). The panelists shone a spotlight on the deadly consequences of lacking diversity in disease research, and discussed topics such as building patient trust, effective community engagement, what resources are needed to make an impact, and actions scientists and supporters can take to help.

“As we all know, diseases affect people differently, and drugs affect people differently,” noted Dr. Aiyar. “That means that a one-size-fits-all solution and more importantly, one-size-fits-all research is not going to give us the answers we need. The only way that we can account for these differences and deliver on the promise of precision medicine is to ensure that our disease research and our clinical trials are inclusive of all populations impacted by disease.”

“Health outcomes are based on more than our genomes: disparities in outcomes are almost overwhelmingly due to the socioeconomic policies, biases, and racism that exist in society,” added Dr. Greally. “What we can and should do in terms of research is to try to bring the same amount of genomic insights to all populations so that we can provide the same care to everybody, no matter their ancestry.”

How does the lack of diverse research impact patients when it comes to treatments?

“Many minoritized populations have been excluded from research. And as a result, we have a biased understanding of disease and treatments that do not work for everyone who needs them,” remarked Dr. Aiyar.

“A Black woman is 22% more likely to die from heart disease than a white woman, and 71% more likely to die from cervical cancer,” she continued. “Before COVID, less than 5% of NIH funded respiratory research reported inclusion of racial or ethnic minorities.”

When minorities are excluded from research, new treatments may not work for them. On the flip side, already-developed treatments can be harmful or even deadly.

“In the Bronx, we talk about ‘ABCD’ being the priorities in terms of healthcare: asthma, blood pressure, cancer, and diabetes,” noted Dr. Greally.

“The treatment of asthma using the standard bronchodilators that relax the muscles of the airway and prevent spasm work much better in some ancestry than others,” Dr. Greally explained. “The non-responsiveness to albuterol, which is our first line treatment, is about 47% of people who identify as African American and 67% of Puerto Rican kids. It’s about 20% for people who are Northern European white.”

These differences underscore the need for more inclusive and precise research.

“We have this designation of ‘Hispanic,’ within which we have Mexican-American, Puerto Rican Americans, and others with widely divergent differences in terms of how they would respond to asthma inhaler drugs, which just shows you how limited the information we collect is in terms of ancestry to allow precision treatment,” Dr. Greally said.

“Unless we study [diverse groups] we’re not going to understand where we could be doing harm with these sorts of medications.”

How does a lack of diversity affect our understanding of human biology?

Dr. Gunawardane’s team aims to understand how cells become diseased, and to do this, they first must define how a normal, healthy cell looks, and that can differ across the population.

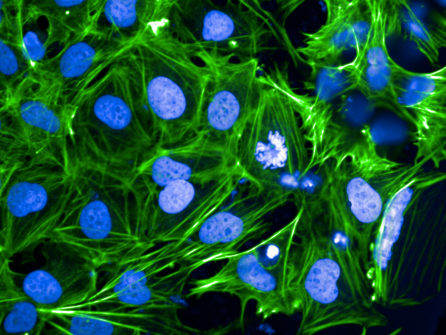

“We are trying to understand how a normal cell works with imaging, gene editing, and all the cutting-edge technologies we have right now,” she said. “But I think we can look around and say, how do you define normal? We really need to define that better before we even can think of what abnormal or pathological really means. That’s where stem cells come into play.”

“Our model system is stem cells because they are more ‘normal’ than a lot of the cells we have used in basic research in the past. The problem right now is that the tools that we use for understanding what ‘normal’ is do not capture the actual diversity in the population.”

Dr. Gunawardane stressed that diversity can’t be an afterthought for experiments like these.

“[The scientific community] often doesn’t really think of diversity as a criteria when we pick cell lines for our experiments,” she lamented. “If there are pathways, like John was talking about, that are affected in a specific population that isn’t included in our work, we don’t even know there are differences there. To get to personalized medicine, it has to start from the basic foundation and work our way up all the way to testing drugs in humans.”

Through ASAP’s Global Parkinson’s Genetics program, Dr. Riley is aiming to better understand Parkinson’s disease – which can have more severe effects in ethnic minorities – by expanding research to include a broader patient pool.

“We are building the most ancestrally diverse genetic database for Parkinson’s in the world. So the mission here is to dramatically expand our understanding of the genetic basis of Parkinson’s disease, which is a global issue, and to make that knowledge globally relevant,” she explained. “We are on pace now to genotype over 150,000 ancestrally diverse participants.”

How does NYSCF foster more inclusive stem cell research?

The NYSCF Global Stem Cell Array®, NYSCF’s automated technology that can make stem cells from hundreds of samples at a time, was created to represent genetic diversity in a vast biobank of stem cell lines, allowing researchers to assess personalized disease traits and drug efficacy.

“More than a decade ago, we started building the infrastructure that would enable us to scale up studies of individual cell lines to the population level,” explained Dr. Noggle, who was instrumental in developing the Array. “Studying diseased cells across as many individuals as we can will be imperative for precision medicine.”

“One good example is a study of Alzheimer’s disease that we’ve done with David Bennett (Rush University) and Tracy Young-Pearse (Brigham and Women’s Hospital) showing we can faithfully represent a late onset form of the disease in stem cell models,” he said. “We were only able to see differences between Alzheimer’s patients and controls when we looked at a large enough population. There’s lots of biology that we think we can capture by looking at populations.”

Expanding NYSCF’s biobank to include more diverse cell lines is an ongoing effort that Dr. Noggle stresses is critical for all future research.

“We’re actively aiming to expand the diversity of the cohorts we use in our studies to enable more inclusive research,” he remarked.

How can we build trust in minoritized communities to encourage participation in research?

“A lot of minoritized communities rightfully have a mistrust of biomedical research due to atrocities and mistreatment by the medical community, ranging from the Tuskegee syphilis trials to the legacy of Henrietta Lacks, and more,” noted Dr. Aiyar.

The panelists stressed that the most important way to engage minoritized communities is by clearly explaining the intent of a study, what will be done with their cells, and how this will benefit them. It is also crucial to engage in discussions to determine how science can help address the issues that matter most to a community, and ensure that the process is collaborative.

“What I see in my work is that various communities don’t necessarily want investigators to come in, take samples, and then you never hear from them again,” noted Dr. Riley. “There needs to be a give and take. We know that we need samples for research and that there’s a lot to be gleaned from them, but then, what do those communities receive back? How are the benefits of research or what is being sought after really being explained to those communities?”

“We need to think about how we are engaging with various communities, how we are working with community leaders to ensure we’re not making empty promises,” she continued. “Taking the time to explain to them why [the research] is being done, what they’ll be getting from it, and what their data or their material will be doing for research, is an important starting point.”

“Our approach at Montefiore and Einstein is simple: we’re defining principles of how we should be doing genomics with our community, not on our community,” added Dr. Greally. “If our community representatives say, for example, that what they care about is asthma, then we’ll study asthma.”

“We have to get away from some of our traditional models for research in which it’s people like me with a big NIH grant who ultimately make decisions about people’s data.”

Dr. Riley emphasized the need to create and leverage infrastructure for continued engagement and effective communication between patient communities and researchers.

“Doing this worldwide takes a lot of coordination,” she continued. “It also requires working with communities on the ground. So it’s not coming into every country and saying ‘Hey, give us all your genetic material,’ but working with infrastructure that’s in place or building infrastructure with local universities to bolster what they have and provide what they may need to enable this work.”

“This is everything from making sure you have materials in the languages that are relevant for that area to making sure you’re actually bringing everyone on board with how data is being collected, disseminated, and shared across borders. All of those discussions must be held up front to make the process run smoothly.”

Getting people excited about science can hopefully encourage broader participation and foster trust as well.

“If you can get people curious, then that’s a way to communicate,” she continued. “It’s not [a situation where we say] ‘you give me this so I can do my research.’ It’s more like, ‘look what we are learning! Look what stem cells have allowed us to do!’ Things like examining a beating heart cell in a dish – that’s exciting, even for me. We have to apply education and open sharing on a broader level.”

NYSCF’s extensive education and outreach curriculum is designed to broaden access to science education for all. Learn more about these programs here.

How can scientists make their research more inclusive?

“Building transparency into the research that we do, and putting into place programs to communicate the results that we find is critical,” noted Dr. Noggle. “The other thing is to try to eliminate barriers to participation: there’s often a desire to try to build our cohorts using very strictly defined criteria, but a lot of that criteria can unwittingly exclude certain groups. So we really have to reassess that criteria and how we enter people into studies.”

“I think as you’re choosing your cell lines for your studies, make the extra effort to choose cell lines that are diverse,” added Dr. Riley. “There are tons of white male cell lines: choose a female or a minority. This can be hard for many of the diseases that we study because a lot of those lines simply don’t exist yet. But where they do exist, I think making that extra effort to incorporate them is really important.”

Why is resource sharing and collaboration important for fostering diverse research?

To enable truly inclusive research, partnerships between researchers and a willingness to share data and resources will be critical.

“Our approach [at The Allen Institute] is based on sharing: whether that’s our tools or how we do our work. We don’t always want to wait for publications [to disseminate our findings],“ remarked Dr. Gunawardane.

“Also, this kind of work is not easily funded,” she continued. “So we have to make this data, and the tools we generate available to the research community at large.”

Different groups have different strengths: combining them will accelerate precision medicine for all. NYSCF aims to foster this kind of collaboration across the research community by making our stem cell lines from diverse populations and technological capabilities available to scientists worldwide.

“We can go and obtain the samples, and do all the consent, but we don’t have the expertise to generate the lines like Scott has done,” said Dr. Gunawardane. “I think partnering and collaborating is absolutely the key.”

Collaboration can also help scientists establish relationships with communities they hope to study.

“Working with disease foundations has been important for us because they have built trust with their patient populations, and that can help with recruitment,” noted Dr. Noggle.

How can we take action together?

“I would love to see, from the funding perspective, a vision for ongoing support for maintaining those relationships in the community,” added Dr. Noggle. “As we turn our thinking from just going to collect a sample to fostering long-term communication, long-term support will be necessary to maintain that back and forth.”

“I think there needs to be a willingness to have strategic partnerships,” stressed Dr. Riley. “As funders, we are very willing to align and tackle different problems together, there are more and more joint funder efforts that need to be supercharged to enable this kind of work.”

“This kind of work always tends to end up as a side project,” said Dr. Gunawardane. “These are not things that some of us haven’t thought about before, but it just hasn’t always been a priority. So I think making this a priority, and providing resources is so important. Otherwise it just won’t get done.”

“I think we need to be encouraging people to step up and to engage in this conversation,” remarked Dr. Greally. “I think that the simple thing to do, because it’s a deliverable for your community that you’re engaging with, is to engage by disease. If there’s a disease I know has a particular prevalence in this community, let’s focus on that. Let’s talk to that community and try to figure out how to address that disease with them.”

“To those of you who are not actively practicing science, we certainly encourage you to use all of the channels available to you to advocate for funding and resources to support diverse, inclusive research,” concluded Dr. Aiyar. “We have the technology and the momentum. We really just need the resources to get it fully in place.”

Additional Resources:

It’s time to incorporate diversity into our basic science and disease models by Rick Horwitz, Ekemini A. U. Riley, Maria T. Millan & Ruwanthi N. Gunawardane (2021) Nature Cell Biology

The Lack of Diversity in Biomedical Research has Deadly Consequences by Jane Beaufore and Raeka Aiyar, NYSCF.org

Using human pluripotent stem cell models to study autism in the era of big data by Ralda Nehme & Lindy E. Barrett (2020) Molecular Autism

Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities, Alicia R. Martin, Masahiro Kanai, Yoichiro Kamatani, Yukinori Okada, Benjamin M. Neale & Mark J. Daly Nature Genetics

Alzheimer’s Trials Exclude Black Patients at ‘Astonishing’ Rate by Robert Langreth & Madeline Campbell, Bloomberg