Tackling COVID, Promoting Health Equity, and Delivering on the Promise of Regenerative Medicine: Highlights of the 2020 NYSCF Conference

News Video Watch COVID-19 Talks & Panels Watch Racial Health Disparities Panel

“My oldest son, Andrew, is a cancer survivor,” said Tony Coles, MD, PhD, CEO of Cerevel Therapeutics. “He was afflicted with non-Hodgkins lymphoma when he was 13 years old. I’d been in the biopharmaceutical industry for probably 10 years by the time Andrew was diagnosed.”

“Because he was receiving chemotherapy, he needed an injection of Neupogen to make sure he could maintain his white blood cell count and stave off infection,” Dr. Coles continued. “I, as the trained healthcare professional, reached into the refrigerator and grabbed the vial, and as I stood there with the refrigerator door open preparing to give him his first shot, it dawned on me that in that vial was the prospect of, potentially, his life or his death.”

It was this moment, said Dr. Coles in his Fireside Chat at the 2020 NYSCF Conference, that made him realize the importance of the work that researchers and drug developers are doing.

“This is not abstract work. There are people on the other end of everything we do in this industry. Every time I walk into the office, I am reminded that there are families waiting for the work we’re doing today.”

This drive to help patients is what compels scientists across the stem cell field, and highlighting promising translational research is the focus of the annual NYSCF Conference. At this year’s meeting, held virtually, participants shared the latest findings from their labs, progress in addressing COVID-19, strategies for combating racial health disparities, and a vision for the future of regenerative medicine.

Stem Cell Scientists Turn Their Attention to COVID-19

One of our greatest scientific needs right now is an effective toolkit to diagnose, treat, and possibly prevent COVID-19, and this year’s conference included a panel discussion celebrating the tenth anniversary of the NYSCF – Robertson Investigator Program where alumni of the program shared their groundbreaking and impactful work to understand COVID-19 pathology, leading to solutions that are accessible to the entire population.

Bottom row: Drs. Jay Rajagopal, Deepta Bhattacharya

“I became interested in COVID-19 relatively early on for personal reasons,” recalled NYSCF – Robertson Stem Cell Investigator Alumna Shuibing Chen, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine. “It was the New Year and my mom was hospitalized in China. I wanted to go visit her, but the entire country was shut down. I started thinking about what my lab could do to address the virus with the tools we had.”

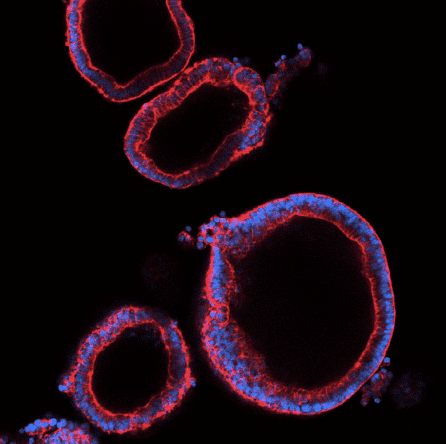

Dr. Chen realized that her expertise in creating organoids – 3D clusters of human tissue made from stem cells – could act as a potent resource for understanding which cell types are most susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection and pinpointing effective drugs. She has since created organoids that model tissues including the lungs, colon, and pancreas, tested over 1200 drugs, and identified several promising candidates to begin moving toward the clinic.

NYSCF – Robertson Stem Cell Investigator Alumnus Jay Rajagopal, MD, of Harvard Medical School, is also interested in discovering which tissues are most susceptible to infection and what puts some people at increased risk of a severe reaction. His group analyzed information gathered through a consortium called the Human Cell Atlas Project that collects and centralizes data on various cell characteristics, many of which are relevant to disease.

“[By examining data from] millions of cells, we could correlate expression [of certain features] to clinical findings,” he explained. “For example, it came up epidemiologically that age, gender, and smoking status seem to affect the course of COVID-19, and all of that started to make sense based on [what we saw] in the lung cells.”

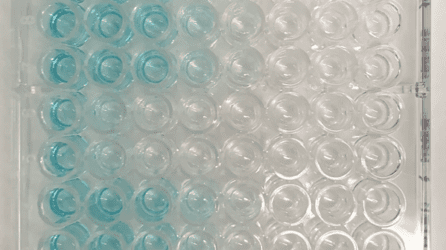

NYSCF – Robertson Stem Cell Investigator Alumnus Feng Zhang, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, focused his efforts on diagnostics, using his revolutionary SHERLOCK technology (which leverages CRISPR gene editing to detect genetic signatures of disease) to develop a rapid, low-cost test.

“Since April, we’ve begun developing a cartridge that you can load reagents into, and then all you have to do is add the samples [collected from a patient] and insert the cartridge into a low-cost machine to get a readout back,” he explained.

While improving diagnostics and treatments is of critical importance, the big question on everyone’s mind remains: how close are we to a vaccine?

“Thankfully, what we’ve been finding is that even though things can go badly at the beginning for a subset of people with severe cases, the durability of the antibody response looks pretty good,” noted immunologist and NYSF – Robertson Stem Cell Investigator Alumnus Deepta Bhattacharya, PhD, of the University of Arizona. “There seems to be nothing particularly unusual about immunological memory and our ability to form it [in response to COVID-19]. Most of our successes [for vaccines] come when there is a normal response to a natural infection, so I think this bodes pretty well for the prospect of getting an effective vaccine.”

While the pandemic has made many aspects of science more difficult, the panelists agreed that the widespread collaboration across fields brought on by COVID-19 gives them hope for the future and has even made them rethink what their labs are capable of achieving.

“[This pandemic] has made me more fearless in my science,” remarked NYSCF – Robertson Stem Cell Investigator Alumna Kristen Brennand, PhD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who moderated the discussion. “I’ve always put myself in a pigeonhole of ‘psychiatric genetics,’ but I realized that we have tools that can span across diseases, and that has really challenged me to think about the kinds of questions we can answer.”

The panelists aren’t the only ones pivoting their work to address COVID-19: scientists throughout the conference shared how their labs are making strides to combat the pandemic:

-

- Chuck Murry, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington is examining SARS-CoV-2’s effect on the heart, finding that the virus can cause electrical and chemical dysfunctions contributing to enduring heart dysfunction

- Madeline Lancaster, PhD, of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology is studying how the blood-brain barrier (the boundary between circulating blood and the nervous system) can become susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, potentially disrupting this crucial blockade and leading to the neurological symptoms that have been observed

- Kristina Dobrindt, PhD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai is examining how common genetic variants may impact one’s risk of developing COVID-19

- Fadi Jacob, an MD/PhD candidate in the lab of Hongjun Song, PhD, at Johns Hopkins University is using organoids to explore how the virus impacts the brain: specifically, a region called the choroid plexus that produces cerebrospinal fluid, the liquid that bathes the brain and spinal cord

Overcoming Racial Health Disparities

Racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by virtually every major disease of our time, and this gap has only been exacerbated by COVID-19. This year, the conference featured a panel discussion that explored how we can all work together to mitigate, and eventually overcome, racial health disparities and ensure that all communities benefit from biomedical breakthroughs.

“Health equity means giving people what they need, when they need it, to reach their optimal level of health,” explained Valerie Montgomery Rice, MD, FACOG, President and Dean of Morehouse School of Medicine.

[Top row: Dr. Raeka Aiyar, Susan L. Solomon, Valerie Montgomery Rice; Bottom row: Drs. Monica Webb Hooper, John Greally]

“It sounds like a simple concept, but achieving it is actually quite a challenge,” added Monica Webb Hooper, PhD, Deputy Director of National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health. “It requires a major shift, or even a dismantling of the way systems have been set up. We have to factor in historical and contemporary injustices. Operationally, what it looks like is something that you don’t usually see.”

So how do we move toward health equity at different stages of the scientific and healthcare process? For those conducting disease research, diversity of samples in the lab as well as diversity of patients in clinical trials is of critical importance for ensuring that findings do not just apply to one group.

“[At NYSCF], we always felt it was essential to represent all ethnicities, genders, and ages in our research,” noted NYSCF CEO Susan L. Solomon, JD. “Stem cells present an unprecedented window to basically create, if you will, avatars of all of us. We built the NYSCF Global Stem Cell Array, our robotic system for creating stem cells, with this in mind and are now planning to recruit and collect several thousand diverse patient samples to add to our ethnic diversity biobank so that we can realize the full potential of stem cell research.”

“One of the things that population genetics has told us is that when you include diverse people in your study, you can end up with outcomes which are better in terms of revealing mechanisms of disease and the particular susceptibilities of people,” added John Greally, DMed, PhD, FACMG, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

However, genetics is just one piece of the puzzle, as highlighted with the COVID-19 pandemic, providing all populations with equal access to quality care is a major hurdle that must be overcome. Dr. Greally sees patients in the Bronx, and he understands that high death rates in his community are largely due to socioeconomic and structural issues that pose barriers to care.

“The counterbalance [to genetic studies] is what we’ve seen with the pandemic: one in every 350 people in the Bronx has died of COVID-19. We’re not sure exactly why, but we know the overwhelming issues involve socioeconomics, health disparities, and racism…For example, we hear stories of families not seeking care because they were afraid ICE would pick them up on their way to the hospital…The stakes are much higher for people who are already limited in terms of their ability to cope.”

Dr. Montgomery Rice stressed that even once a vaccine is approved, we must ensure that it is safe and effective for everyone in our diverse community and that everyone can receive it.

“There are two ways you can measure the effectiveness of a vaccine: one is that you give the injection to someone and it produces the antibodies, and they may be immune for a period of time,” she said. “But the other measure of effectiveness involves uptake of the vaccine among those persons who are at greatest risk of the disease. And if we do not do that second one, we will just have a nice vaccine that sits on the shelf, and we will not have eliminated the risk associated with this disease.”

“We have to spend a lot of effort ensuring that we are making the public comfortable,” she continued. “They are not going to come to our nice, shiny buildings. We have to be in mobile vans. We have to go to the community centers. We have to step out of our comfort zone to meet people where they are.”

Moving forward, the panelists stressed the importance of collaboration to enact widespread change.

“This has to be an all-hands effort,” remarked Dr. Webb Hooper. “We must have stakeholders at all levels and all disciplines across organizations contributing to get this work done. I think that all too often, a grassroots organization who are on the ground doing this work daily and have keen insights into community needs are often not included, or if they are included, they’re not equitably included. Equitable engagement with affected communities is a cornerstone of the efforts that will address disparities and move us towards justice.”

Finally, the group recognized the importance of seeding the pipeline for diverse researchers, clinicians, and administrators who will recognize the severity of health disparities and advocate for better practices.

“When you have diverse persons in the room and people who are able to really participate in understanding others’ circumstances – even if they have not lived them, because they have made themselves aware – that is when we get the rich solutions. That is when we get the solutions that are going to be inclusive of others,” said Dr. Montgomery Rice.

Regenerative Medicine: Lessons Learned and a Vision for the Future

How can we accelerate the path of a cell therapy from the lab to patients? At a panel discussion on regenerative medicine, experts who have traveled this path shared sage advice on translating scientific findings to meaningful therapeutics, key elements to progress to the clinic, roadblocks they have overcome, and a vision for the future of the field.

Anthony Johnson, CEO of Kodikaz Therapeutic Solutions, shared his company’s work to target cancer with a technology that can zero in on affected cells.

“Our technology is called Zip-Code Technology, and it’s able to specifically target and deliver a variety of payload capacities to cancer cells,” he explained. “Our initial focus areas are pancreatic cancer and multiple myeloma, but we show the same phenomenon [that Zip-Code Technology targets] to also be present in non-small cell lung cancer as well as colorectal cancer.”

Carl June, MD, detailed his experience (both as a panelist and as the conference’s keynote speaker) as a pioneer in development of CAR-T therapy, which became the nation’s first FDA-approved personalized cellular therapy for cancer in August 2017 and has saved countless lives. He is optimistic about what will be possible in the future of precision medicine.

“I think we’re at a really great time in science because of what’s now possible. There’s work coming from biotechs and universities that didn’t happen in previous drug development because that process was usually handed off.”

For Rachael Pearson, PhD, of University College London, one of the most crucial aspects for bringing cell therapies – like the ones she is developing to treat blindness caused by retinal degeneration – to the clinic is input from people with different skills and backgrounds.

“I think the key is collaboration,” she noted. “None of us alone can achieve all of the necessary components to take something through from first concept to clinical trials, so I think it’s really important to build a good team, also to try to get clinicians involved early on, because I can develop therapies to cure mice of blindness, but it’s a whole different ball game to then translate that to patients.”

Irv Weissman, MD, Director of the Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford University, whose pioneering work isolating blood-forming stem cells in humans was a groundbreaking discovery that, along with his more recent discoveries in immuno-oncology, have lead to transformative regenerative medicines, stressed that for researchers of all career stages, it’s important to think critically about experiments.

“I always tell this to my students: don’t believe what you read in textbooks. Make sure you look at the experiments.”

He also shared the importance of encouraging medical students to engage with research.

“We shouldn’t think of medical schools just as trade schools where your apprentices learn what was done in the past,” remarked Dr. Weissmen. “[When I was in medical school], you went six days per week, but you had a half day every day to do something else. And that was incredibly productive in bringing up physician-scientists.”

Chuck Murry, MD, PhD, whose lab at the University of Washington is working toward cellular therapies for heart disease and recently transitioned their latest stage program to Sana Biotechnology, stressed that for science to move forward, effective communication to regulators and the public is key.

“I would encourage the young people out there to not hang their citizenship at the door,” he said. “It is so important that members of the scientific community serve as spokespeople and as advocates for science. Invite legislators to come to your laboratories and tell them what it is that you’re working on. Teach them about genome editing or stem cells. And when they see that there are reasonable people doing things for the public good, science becomes less scary.”

More Highlights

- Christine Mummery, PhD, delivered a plenary lecture on her efforts to improve the drug discovery process for heart disease and how she is employing stem cells to test drug safety and efficacy

- Helen Blau, PhD, of the Stanford University School of Medicine shared how her lab is studying the heart failure that can occur in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and linking it to the size of telomeres, structures at the ends of chromosomes

- Sylvia Boj, PhD, of Hubrecht Organoid Technology described her lab’s work creating organoids – 3D clusters of human tissue made from stem cells – that model the colon, lung, breast, pancreas, and ovary for the study of cancer, cystic fibrosis, and other diseases

- Simon Tavaré, PhD, of Columbia University detailed his research into why some patients do not respond to cancer immunotherapies called checkpoint inhibitors

- Ed Boyden, PhD, of MIT described methods for imaging the brain, including a strategy that uses fluorescent reporters to measure activity of neurons

- Ron Evans, PhD, of the Salk Institute shared how his lab has created islet-like organoids – 3D clusters of human tissue that model cells in the pancreas – to explore options for cell replacement therapies for diabetes

- Dieter Egli, PhD, of Columbia University detailed his lab’s recent finding that gene editing in human embryos may result in an unexpected hazard – deletion of entire chromosomes – that must be addressed before this practice moves into the clinic

- Wei Li, PhD, of Cytovia Therapeutics described Cytovia’s work to create genetically engineered cells called ‘natural killers’ from stem cells to target cancer – a project they are working on in partnership with NYSCF

- Andrew Gaffney, PhD, of STEMCELL Technologies reported on the critical topic of quality metrics for stem cell research based on studies STEMCELL Technologies have conducted with surveys across the scientific community

- Bjarki Johanesson, PhD, of The NYSCF Research Institute presented results that will be published in collaboration with Google Research to develop an artificial intelligence-driven imaging platform to detect disease features in skin cells

- Steven Goldman, MD, PhD, of the University of Rochester shared his work toward cell therapies that replace diseased glial cells (critical support cells) in the brain with functional ones derived from stem cells to treat diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s, or schizophrenia

- Enakshi Sinniah, a PhD candidate in the lab of Nathan Palpant, PhD, at the University of Queensland shared her lab’s work to understand how epigenetics – changes in your behavior or environment that affect how how your genes work – impact cell identity